Europe’s hotel industry has welcomed the rollout of the EU’s Digital Markets Act, which was announced last October and is now fully in force.

NB: This is an article from Triptease, one of our Expert Partners

The DMA brings in EU-wide legislation to rein in the power of online gatekeepers like search engines, social networking sites, and – you guessed it – OTAs. The legislation is designed to hand power back to the businesses that have come to depend on these extremely powerful gatekeeper platforms.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter and stay up to date

With a clear list of ‘dos and don’ts’ (as well as some seriously hefty punishments for breaking the rules), it’s hoped that the DMA will force OTAs ‘to behave like partners, and not as gatekeepers.’

Here’s what it means for hoteliers at a glance:

- OTAs will be required to hand over far more data about your hotel listings (including their performance on metasearch and paid search)

- OTAs will be banned from punishing hotels who offer better rates on their direct sites (no more dropping down the ranking)

- Any platform breaking the rules could be fined up to 10% of their worldwide turnover (for Booking.com, that would be over $1 billion).

But how will the legislation actually be enforced? Does this mean price parity is a thing of the past? And what does this mean for hoteliers outside the EU?

We’ve combed through the detail so you don’t have to. Keep reading to discover what the Digital Markets Act might mean for your hotel.

What is the Digital Markets Act?

The Digital Markets Act is a piece of EU legislation designed to ‘put an end to unfair practices by companies that act as gatekeepers in the online platform economy.’

By ‘gatekeepers,’ the EU means those large digital platforms that sit between business users and their customers – think Google, Amazon, and Booking.com. The EU asserts that the position of these platforms ‘grant[s] them the power to act as private rule maker[s]’ and clamp down on competition.

Sound familiar? For decades now, hoteliers have felt the pain of OTAs like Booking.com acting as ‘private rule makers’ and imposing what many feel are unfair conditions on the businesses using their platforms.

From price parity clauses to the fact that OTAs hoard user data (preventing hoteliers from owning the guest relationship), the hotel industry has long been crying out for measures to restore balance.

The 2022 HOTREC hotel distribution study found that most hoteliers (55%) in Europe feel pressured by OTAs to accept terms they would not voluntarily offer to guests. This could be things like preferential cancellation policies or special discounts for OTA loyalty members.

The DMA has been brought in with the aim of curbing these pressures and handing power back to the business users – in this case, hotels – who ultimately provide the products behind the gatekeeper platforms.

What are the ‘dos and don’ts’ of the Digital Markets Act?

The EU has issued a framework for the obligations that gatekeeper platforms will have to abide by. Here are the most pertinent ones for hotels:

DOs

- Platforms will be forced to allow their business users to access the data that they generate in their use of the gatekeeper’s platform.

- Platforms will also have to provide the companies advertising on their platform with access to the performance measuring tools that they themselves use.

- They will also have to allow business users to promote their offers and conclude contracts with their customers outside of the gatekeeper platform.

We’re yet to see the specifics of how this pans out with hotels and OTAs in particular, but in theory this could lead to hotels in the EU being provided with much more data on the performance of their listings on OTA platforms. It could also spell the end of price parity clauses (more on that further down).

DON’Ts

- Platforms will be banned from treating their services and products more favorably than similar services or products offered by third parties on the gatekeeper platform.

- They will also be banned from preventing consumers from linking up to businesses outside their platforms.

Again, we don’t yet know the particulars of how these bans will affect OTAs – but the legislation is clearly designed to give businesses more ownership over their relationships with end users.

And there are hefty sanctions in place for ignoring these new rules. The legislation states that:

- Non-compliance could incur fines equalling 10% of worldwide turnover

- Repeated infringements would result in that amount increasing to 20%, and periodic penalties of 5%

- The Commission will impose additional remedies for ‘systematic infringements,’ which may include restructuring the company in question.

When will the Digital Markets Act start to impact OTAs?

So far, so exciting – but how soon will we begin to see the results of this new legislation?

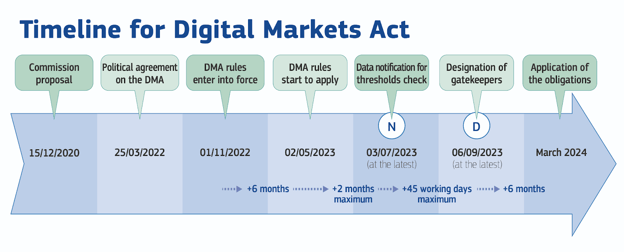

The rules of the DMA were implemented in November 2022, and began to fully apply as of May 2, 2023. We’re now entering the two-month period where potential gatekeeper platforms will have to inform the Commission of the services which fit their criteria.

Source: European Commission website

Once the gatekeeper platforms are designated, they will have six months to comply with the DMA’s requirements – which takes us up to March 2024.

But it’s not time to pop the champagne just yet. It’s anticipated that the EU will be faced with plenty of legal challenges related to gatekeeper designations. As one legal commentator points out, ‘the obligations [of the DMA] may need to be “translated” for each gatekeeper to be able to apply the rules in practice’ – making it ‘a lengthy process prone to litigation.’

How might the Digital Markets Act benefit hotels in the EU?

We’re now set for a period of ‘wait and see.’ When the legislation was first announced, Booking.com responded by cautiously welcoming many of its recommendations – but expressing concern about others. We don’t yet know how the Act’s obligations will be ‘translated’ for each gatekeeper, or how different platforms may challenge it in court.

But there’s certainly reason for optimism. The DMA is a clear statement of intent from the EU to rein in the powers of enormous digital platforms like OTAs. Let’s take a look at what it might mean for hotels.

Increased transparency

As a hotelier, one of the real frustrations of working with OTAs is the minimal access to data. OTAs spend huge amounts of money advertising your hotel on ads and metasearch – but you as a hotelier don’t know who clicked those ads, what demographics they fall into, and whether they went on to book your hotel.

Without access to this kind of data, it can be very hard to determine the volume of your OTA bookings that are truly incremental (and whether OTAs are attracting potential guests to their platform using your hotel, only for them to ultimately book a different property).

With the DMA in force, though, hotels in the EU may well be about to enjoy access to far more of this kind of information. The legislation states:

Business users [i.e. hotels] that use core platform services provided by gatekeepers [i.e. OTAs], and end users of such business users [i.e. guests] provide and generate a vast amount of data. In order to ensure that business users have access to the relevant data thus generated, the gatekeeper should, upon their request, provide effective access, free of charge, to such data. […] Gatekeepers should also ensure the continuous and real time access to such data by means of appropriate technical measures.

In theory, this would allow hotels in the EU much more scope to request information about how their hotel name, content and ARI feed are used by OTAs.

We might be moving towards a world where your OTA partners would be required to tell you:

- what they spent on SEM and meta using your hotel name

- how many clicks and bookings those listings generated

- how many times ads for your hotel resulted in the OTA taking a booking for another property.

And with a specific provision that mandates the same level of access for ‘third parties contracted by the business user,’ you would be able to put such data to use in other areas of your marketing tech stack.

When the DMA reached full political agreement back in May 2022, HOTREC’s Markus Luthe commented that OTA data retention had been acting ‘as a disincentive for the digitalisation of hotels […] and entrench[ing] the dependence of hoteliers towards OTAs.’ While we’re yet to see how major OTAs will fulfill the DMA’s obligations in practice, the European hotel industry definitely has reason to be cautiously optimistic about a more informed, independent future.

Freedom to offer the best rate direct

Here’s the part that got hoteliers talking when the DMA was first introduced. The legislation states that:

… it should not be accepted that gatekeepers limit business users from choosing to differentiate commercial conditions, including price. Such a restriction should apply to any measure with equivalent effect, such as increased commission rates or de-listing of the offers of business users.

In other words, OTAs should no longer be able to impose narrow price parity clauses on their EU hotel partners.

However back in September 2022, Skift questioned the likely impact of such a ban – pointing out that when Austria and Belgium banned both narrow and wide parity clauses, ‘it did not lead to significant changes in the way hotels distribute their rooms.’

We’re yet to see how the DMA affects price parity in practice – but we’ll certainly be keeping a close eye on pricing and distribution trends over the next six months.

What about hotels outside the EU?

We’ve arrived at the fun part – the thorny issue of cross-border digital regulation.

The Digital Markets Act was introduced by the EU in order to regulate large gatekeeper platforms without those platforms having to adopt a new approach for every member state. But what about when it comes to outside the EU? Does the DMA also spell changes for hoteliers in the UK?

Now, it should probably be noted at this point that issues of digital platform regulation across different territories are extraordinarily complex and fast-moving. We don’t yet know how OTAs being forced to act a certain way in one territory will impact their behavior in others. But here’s what we do know about similar legislation in the UK:

The UK’s DMA equivalent

In April 2023, the UK government published their Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill. Rather than ‘gatekeeper platforms’ – the terminology used by the EU – the UK bill refers to digital platforms with so-called ‘strategic market status’ (SMS). It’s expected to enter into force in Autumn 2024.

The UK Bill differs from the DMA in several key respects. First off, as legal commentators at Sidley have noted, ‘the UK designation process is proposed to be based on a participatory and discretionary model, [while] the EU approach is regulation-driven.’

In other words, the UK will engage with potential ‘SMS’ companies from the outset to assess their status (a move that emphasizes the ‘participatory and collaborative’ approach they want to encourage between the government and SMS firms).

Secondly, rather than the universal ‘dos and don’ts’ imposed by the DMA, the UK Bill will introduce a bespoke code of conduct for each SMS firm – one that ‘addresses the particular harms associated with [their] activities.’

So, while the UK Bill is lagging behind the DMA in terms of timescale, it’s possible that this more bespoke approach will lessen the risk of legal challenges and ensure a smoother path to enforcement.

Hotels and OTAs: A new era?

As these new laws begin to come into force, one thing’s for certain: the landscape for hotel-OTA partnerships is set to change. (And the same could soon be true for US hoteliers too – the American Innovation and Choice Online Act covers similar ground).

Here at Triptease, we’ll be paying close attention to how things play out. The all-in-one Triptease Data Marketing Platform was been built specifically to help hotels increase their direct bookings, offering the kind of data sophistication and real-time personalization that OTAs take for granted. Here’s hoping that this new regulatory era will put even more power back into hoteliers’ hands.