Attribute-based shopping (ABS) has become the latest buzzword in hospitality. The functionality promises to change the way that travellers search and book hotels, shifting from a few room types to a more targeted search that matches each room to a traveller’s preferences.

NB: This is an article from OTA Insight

The concept of ABS has been around since at least 2008, when Sabre Travel Network presented its new technology for airlines to sell airfares based on attributes, such as seat type or ancillary bundles. This functionality allowed travellers to make apples-to-apples fare comparisons based on certain attributes. Since then, ancillaries have ballooned into a massive business: the top ten airlines raked in $29.7 billion in 2017 alone, per IdeaWorks.

Quite surprisingly, consumers didn’t seem to mind paying for things that used to be included in a fare, such as advance seat selection. Average airline satisfaction scores in the US rose steadily from 62 out of 100 in 2008 to 73 out of 100 in 2018. And that’s within a period of unprecedented growth in miles flown and passengers served.

Now, nearly a full decade later, attribute-based shopping has arrived in hotels. IHG has implemented an Amadeus-based ABS approach at 1,000 properties worldwide. Marriott CEO Arne Sorensen recently teased an in-house initiative to implement attribution-based shopping (ABS). On stage at Skift Forum, he said:

“We have a new reservations platform rolling out this year. It’s going to be the ability to identify your room when you’re booking, choose more room types than in the past. We will have bed type, views, floor, all of those sorts of things.”

While ABS worked wonders for airline revenues, it’s not abundantly clear that it will be similarly lucrative in hospitality. Hotel rooms have more potential attributes than the average airline seat, which makes for complex mapping at the property level. Transitioning to ABS requires a significant technical investment to re-classify room inventory and make it searchable in a way that makes intuitive sense for guests.

Will there be a similar uptick in revenue thanks to more personalised bookings? Will guests differentiate enough value from hotel-selected attributes to pay more for certain rooms? And will guests want to sort through so many hotel-specific attributes when comparing one hotel to another? These are questions that must be answered before investing in the technical Infrastructure required for ABS.

Less is more – or more is more

By creating an uneven comparison between hotels, attribute-based searches could complicate a traveller’s ability to compare hotels directly. Additional attributes could also further contribute to an overwhelming number of results in a given search. If hotel brands prevent OTAs from offering attribute-based shopping – as part of ongoing efforts to encourage direct booking – it will affect how a traveller compares and contrasts competing hotel options. In this view, choice would be artificially limited through opaque determinations of a given hotel room’s attributes.

For example, if a user compares two hotels for a stay in New York City, how can a comparison be made for a Standard King room at Hotel A and an attribute-based room at Hotel B that prices a preference for a high-floor room away from the elevator? Or if Hotel A is an attribute-based hotel, how can a traveller compare two hotels that have either mapped attributes differently or have dynamically priced similar attributes at different prices? There’s an opacity that greatly complicates how a traveler searches for a room.

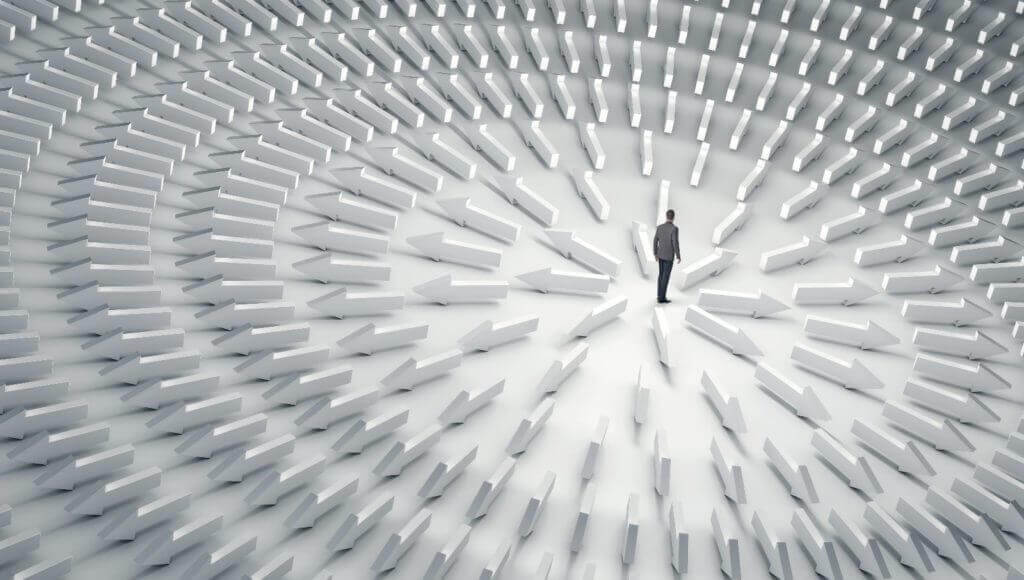

Attribute-based shopping brings out a familiar conflict: do consumers want more choice, such as searching across many hotels for a given search on OTAs or metasearch, or do they prefer to have their hotel options artificially limited to make them more manageable, such as choosing one hotel to book direct?

In the influential book, The Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz makes a compelling argument as to why “less is more”. Today, more than 14 years later, this argument remains persuasive in the face of today’s algorithmic “personalisation”. Travel brands must simultaneously offer more choice than ever and deliver the personalised filtering that reduces these choices according to a user’s preferences, chosen filters, and trip characteristics.

The book identifies two approaches to decision-making: “maximisers” and “satisficers”. The maximisers want to be sure a given purchase is the best one, so they research exhaustively until the choice is certainly the best. Satisficers have standards and are comfortable choosing a product or service that fulfils those needs without exhaustive research.

Attribute-based shopping hinges on its ability to support both maximisers and satisficers. Maximisers should be able to search deeply to find the best choice for them, while satisficers should have sufficient trust in the algorithm to personalise a given search. For both cohorts, past behaviour must be the filter that personalises results.

When it comes to choice, it’s fairly easy to go too far: look at supermarkets, who saw a proliferation of products, or stock keeping units (SKUs), that resulted in fewer sales. In reducing the assortment across 94% of categories, some stores saw an 11% increase in sales and 75% of households increased their spending. In this case, more is not better; it’s about the right product mix that converts the target demographic more effectively.

“When approaching ABS for your hotel, keep the supermarket in mind. Fewer SKUs, targeted to the right demographic and presented in an easy-to-understand interface, may be more powerful,” said Sean Fitzpatrick, CEO of OTA Insight. “Understand what drives decision-making for your audience. Too many attributes may lead to choice paralysis – and push certain guests towards ‘simpler’ channels when searching and comparing hotels.”

The downstream impacts of ABS

Attribute-based selling challenges revenue managers to be more nimble when rate shopping. ABS makes it more difficult to achieve a true apples-to-apples comparison when building a competitive set.

For example, if your hotel has 15 floors and most of your competitors have taller buildings, how will you compare rooms priced according to floor level? Who decides which room has a “view” and which doesn’t – or even if a view of the East River in New York City is more valuable than a view of Central Park?

Dynamic pricing may solve some of these issues. Hotels that price individual attributes according to actual consumer demand may see more success in growing incremental revenues without affecting guest satisfaction. Think about the much-reviled resort fee – a blanket application of additional costs without perceived value is not wise. Given this, the introduction of ABS will necessitate a corresponding shift in strategy.

Some things to consider:

- Competitive set: As hotels re-define how to sell rooms, they must also re-define how to create an accurate comp set. We must also map those hotels in a new way to accommodate how a hotel dynamically prices each attribute for a given search.

- Rate insight: Curiosity is rewarded. In pursuit of a comprehensive understanding of where your hotel’s rates stand in comparison to another’s, managers will need a firm grasp on rate trends across markets and their comp set. Dynamic pricing also challenges rate insight, as pricing fluctuates according to not only market and property demand but also attribute demand.

- Content: Deeper integration of amenities into each search requires updated content. Room descriptions should be descriptive and must be mapped more precisely to reflect a room’s given attributes across internal systems and external distribution channels.

- Rate parity: If this newly-attributed content doesn’t get distributed to OTAs, as some in the industry suggest, there will be a real challenge for maintaining parity in the eyes of the consumer. If a hotel offers a standard room at a base price of $199, and that guest can book that room but with a view for an additional $30, plus breakfast for $10, and a room away from the elevators for an additional $20, how will those be shopped? ABS can only really be successful if guests see a consistent rate across all channels, and then pay for additional attributes either during the booking flow or prior to check-in.

- Loyalty: Guests will have even more incentive to stay at familiar hotels. ABS may also encourage more loyalty enrollments, per Google/Phocuswright: “If a travel brand tailored its information and overall trip experience based on personal preferences or past behaviour, 76% of US travellers would be likely or extremely likely to sign up for the brand’s loyalty program.”

When reconciling internal needs with customer expectations, keep a balanced view. As Schwartz, the author of The Paradox of Choice, recently shared in an update to his decade-old concept, it’s about finding the blend that works best for your customers: “The trick is to find the middle ground – the ‘sweet spot’ – that enables people to benefit from variety and not be paralysed by it. Choice is good, but there can be too much of a good thing.”