Although perceived as a service industry, hotels today are essentially a real estate business, with owners utilising guest service as a tool to maximise financial return per square meter.

NB: This is an article by Peter O’Connor, Professor of Strategy at University of South Australia Business School

However, its highly perishable nature (an unsold hotel room cannot be stored and subsequently offered for sale) makes efficient distribution vital to hotel profitability. Each additional sale contributes to fixed costs, making selling each room each night at the optimum price critical to long term success. As a result, most hotels try to optimise distribution efforts to drive additional sales.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter and stay up to date

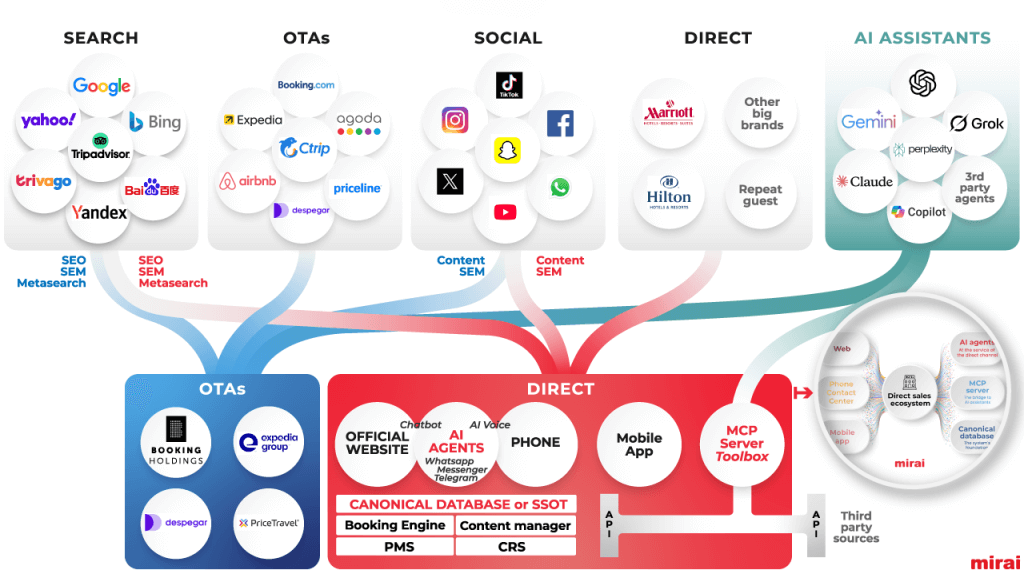

Historically this means working with travel agents, tour operators and destination management organisations to position the hotel in front of potential customers. More recently online platforms known as Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) have emerged as key players in the hotel distribution landscape. These aggregate product data, prices and inventory from multiple sources, helping to simplify the consumer search-and -book process by reduced search cost and transaction friction; providing potential customers with easy access to comprehensive, multi-brand travel information; promoting rate transparency; and frequently offering a better search and book experience. OTAs’ share of hotel online bookings has grown to over 40% in the USA, 70% in China and 60% in Europe. As a result, concerns have arisen as to hotels’ dependency on such online platforms and as to whether their net effect for hotel properties is positive or negative from a financial perspective.

There are multiple advantages of working with OTAs as distribution partners. Firstly, they provide visibility, with participation putting the property in front of, and potentially bookable by, customers difficult to access otherwise. OTAs also reduce the technical and administrative hurdles of online distribution, taking care of issues such as translation, credit card processing and search engine marketing on behalf of participants. Being listed is also low risk as OTAs are pay-per-performance, with commission due only on successful bookings. In addition, studies have shown that exposure from being listed on OTAs results in additional direct bookings through direct channels, a phenomenon known as the ‘billboard effect’. As such referrals do not flow through the OTA platform, they incur no commission and serve as a hidden bonus of OTA participation.

Working with OTAs also has noted disadvantages. Firstly, OTA bookings necessitate the payment of commission, typically between 15% to 30%, reducing profitability on bookings driven through the system. Channel conflict is also a challenge, with critics maintaining that OTAs simply displace bookings, resulting in higher costs for the same volume of business. Working with OTAs also increases complexity, with rates/inventory having to be maintained on multiple systems. Lastly OTA participation can impose certain restrictions that limit flexibility. For example, although now formally outlawed in many regions, rate parity clauses were common in the past, removing price as a competitive lever and limiting hotels’ ability to both yield effectively and drive customers towards preferred booking channels

As a result, the relationship between hotels and OTA could best be described as adversarial. While hotels appreciate the bookings that flow through OTA channels, they resent the associated costs and limitations that working with such platforms entails. Hotels typically prefer to sell their rooms through direct channels. Many provide a best rate guarantee on their direct website to incentivise conversions and drive direct bookings. Several have engaged in high visibility direct booking campaigns, undertaking publicity campaigns to encourage customers to book through direct channels instead of through OTAs. In each case the overall rationale is one of cost reduction, with reduced commissions paid supposedly leading to higher profitability.

However, this viewpoint ignores the additional sales and marketing effort needed to drive such business. To drive direct bookings, hotels need to not only maintain a technological infrastructure (website, mobile app, bookings engine), entailing a range of upfront capital costs, but more importantly invest in gaining visibility in front of customers. These costs are sunk in that, unlike pay-per-performance OTA fees, they must be paid irrespective of whether or not they result in actual bookings. In addition, proponents of direct distribution ignore the additional sales that come from being listed on OTA sites (at least some of which must be marginal), which, while increasing distribution costs because of their associated commissions, increase gross revenues by a larger amount, offsetting the increased transaction costs and resulting in higher overall profitability.

As such, this study aims to bring clarity to this question by empirically investigating the added value of OTA participation for hotel properties and in particular its impact on bottom-line profitability. Unlike previous studies, which have for the most part used a conceptual, theoretical or even speculative perspective, this study makes use of comprehensive, multi-year, financial data to empirically establish whether, on balance, the benefits of OTA participation for a hotel property outweigh the (financial and other) costs. The results should therefore help to clarify whether it is worthwhile to work with online intermediaries in addition to making the economic and administrative effort to drive direct online sales.

Research Methodology

The effect of OTA participation on profitability was examined by analysing the financial results of Belgian lodging properties. Belgium was selected based on its relatively unique legal requirement that all companies, including small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), publish detailed annual financial reports. Our focus was on Return on Assets (ROA) because of the difficulty in establishing the exact costs associated with each form of reservation, due to limitations in the Uniform System of Accounts used by hotels worldwide. These largely fail to record distribution costs (direct or indirect) in a manner that can be used to evaluate either option at the transaction level. However, by considering the overall financial performance of the property in question, such data can be used to evaluate the net effect of participation in OTAs, investigating whether OTA distribution results in a better net economic outcome from the perspective of the hotel property.

The choice of Booking.com was due to its position as the global leader in online hotel booking. Booking.com is the leading OTA in most European countries with an approximate market share in 2019 of 46% of the European indirect online travel market. Research has shown that most hotels that use OTAs as a distribution channel in Europe use Booking.com and thus it is a useful proxy for OTA participation. A list of all Belgian lodging facilities appearing on Booking.com in July 2019 was collected and matched with their published financial data from their date of joining until December 31st 2018. This resulted in a sample of 9,248 firm-year observations relating to 775 unique firms over a twenty-year period.

A two-step system GMM estimation of a regression model of firm-level return on assets (ROA) on participation in Booking.com was used to analyse the data. This contained various control variables identified from the literature, including size, age, leverage, liquidity and lagged ROA. The moderating effect of firm age and size was studied by including interaction variables between the Booking.com dummy and age and size, respectively.

Study Findings

Our findings clearly demonstrate a statistically positive effect on profitability for hotels that participated in Booking.com compared to those that did not. Plugging in the median value for size into our regression equation shows the effect of participation on ROA to be 2.89 percentage points. With a mean ROA of just 3.03 percent for the whole sample, this effect can be considered economically important, suggesting that participation in OTAs is a net positive for hotels and that the resulting revenues outweigh the costs involved since participating hotels are substantially more profitable than those that do not. Given the tight margins that typify the hotel sector, this performance boost represents a key argument as to why hotels should work with OTA partners.

The results also indicate that the positive association is stronger as properties decrease in size. While identifying the underlying causes is outside the scope of this study, we speculate that since smaller properties tend to be owner managed; make less use of technology; and have lower dedicated marketing budgets, participating in Booking.com allows them to be more widely distributed, increasing awareness and allowing them to sell in markets that they could not otherwise have accessed, helping to grow revenues. More importantly, the costs of doing so, traditionally perceived as prohibitive, increase at a slower rate than resulting revenues, leaving participating properties in a more favourable net position.

Overall our results show that the benefits of OTA participation substantially outweigh the costs, resulting in a clear and substantial boost to hotels’ bottom line. This challenges conventional wisdom about working with OTAs, with findings clearly demonstrating that, when all revenues and costs are considered, hotels that work with Booking.com are more profitable, with any direct or indirect costs absorbed by the resulting increased revenues, leading to enhanced financial performance.

For further details, particularly of the research methodology used and findings, please consult:

Abdullah, S., Van Cauwenberge, P., Vander Bauwhede, H. and O’Connor, P. (2022), “The indirect distribution dilemma: assessing the financial impact of participation in Booking.com for hotels”, Tourism Review, https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2020-0101