Twenty years ago, net rates (without any cost or commission) were the norm, and hotels knew the profitability of each of their channels perfectly well.

NB: This is an article from mirai, one of our Expert Partners

It was just a couple of clicks away in their PMS. What hotels did not know, though, was the retail price their properties were being sold for or how much guests were paying for the room. Therefore, hotels blissfully ignored the money they were leaving on the table that tour operators and agencies were taking.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter and stay up to date

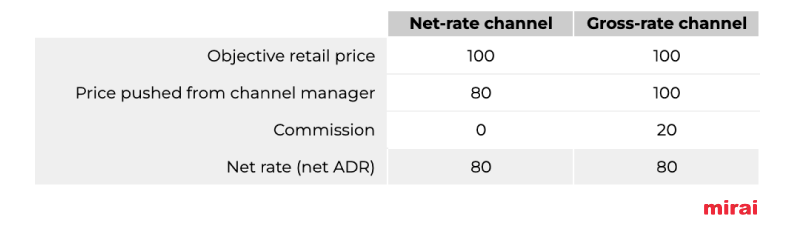

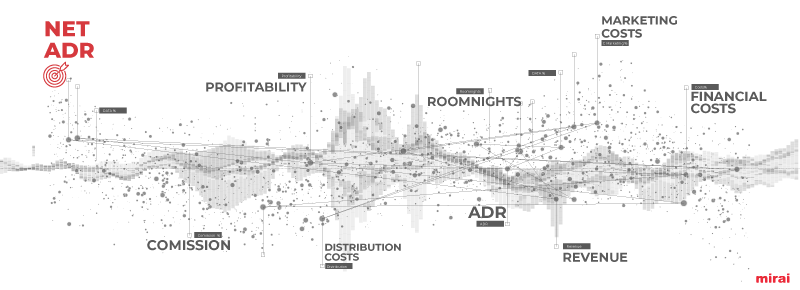

Today, the picture is very different. Although some channels still pay net rates to hotels, such as Expedia’s merchant model, a majority of online channels use commissionable gross rates. With that shift, hotels and OTAs captured much of the business tour operators and agencies once had. On the way, however, hotels lost control of the most important KPI: net ADR.

At first glance, it sounded like a major win with an acceptable toll. And it was. To get the net ADR, hotels simply discounted the commission and that was it. It wasn’t as easy and automatic as it used to be, but it was easy nonetheless.

Unfortunately, new discounts and costs (commissions, marketing and financial) turned that simplicity into a much harder, manual and error prone task. Even today, a majority of hotels ignore how much money they make (and lose) by channel. The difficulty of calculating the net ADR, together with the lack of automation in the PMS industry and RevPAR obsession, pushed the hotel industry to set a new KPI for profitability: “the average commission”. A much easier to estimate KPI but a totally misleading one, with negative consequences leading revenue managers to make wrong decisions such as:

- Favoring channels that appear to be “cheaper” but actually have among the lowest net ADRs in the channel mix. Booking.com is the most relevant example.

- Accepting, without a doubt, every new trick OTAs put on the table. Initiatives that always bear additional discounts or costs, putting more pressure on your already low net ADR.

- Even driving direct bookings thinking it’s the most efficient channel which it is in most of the cases. However, if done incorrectly, it may not be.

A rigorous net ADR analysis, that moves beyond “average commissions”, and that also takes into account discounts and all types of costs, is a core competency every professional revenue manager should have. Such a net ADR analysis should be in the ongoing to-do list of every hotel.

Visibility boosters

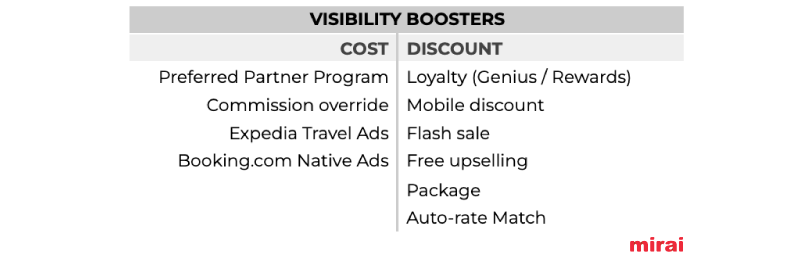

In the last decade, OTAs have been very successful introducing the idea that “visibility” had a “toll”. If you wanted to show up in the top positions in an OTA, you needed to give something in exchange. Many programs with fancy names emerged: Booking.com Preferred Partner, Genius and Native Ads, Expedia Rewards and Travel Ads, mobile discounts and flash sales are just a few examples. Hotels overwhelmingly embraced not just one option but many of them (and even simultaneously) yearning for that promised “incremental visibility”. While doing so, not only did they lose control of their asking retail price but they also lost control of the costs they were paying the OTAs. As a result, net ADRs plummeted without many even realizing.

We can divide visibility boosters in two types:

- “Cost boosters”: hotels pay more to the OTA (higher commission or other fees).

- “Discount boosters”: hotels discount their rate but pay the same commission.

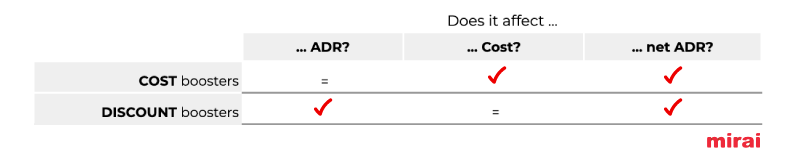

Both boosters (cost and discount) negatively impact the profitability of the hotel (net ADR). In a different way, though. Whereas cost boosters impact the “commission or cost”, discount boosters push the ADR down. What matters is that net ADR is always impacted.

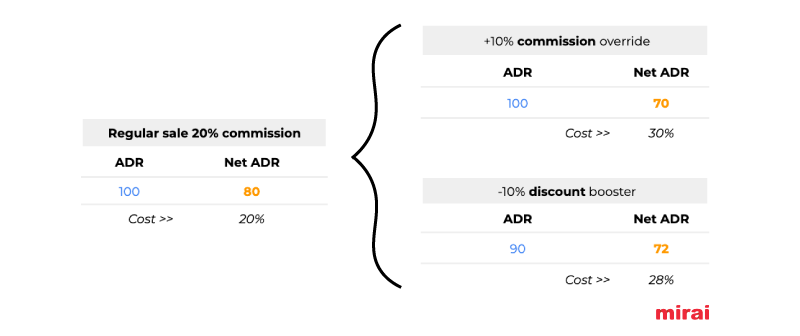

We can see the impact in a simple example:

Despite a similar negative impact on profitability, discount boosters are better perceived by the hotel industry than cost ones because:

- They don’t increase the “cost” or “commission”, the new and misleading KPI for profitability.

- Revenue managers can decide to discount the rate but do not always have the autonomy to increase the channel cost. To do so, they sometimes need a third party approval.