Among the many delicious scenes from the movie “Goodfellas” is one where the characters of Ray Liotta and Joe Pesci burn down a restaurant because its credit has run out, putting an end to their graft. “And then finally, when there’s nothing left, when you can’t borrow another buck from the bank, you bust the joint out. You light a match.”

NB: This is an article from HotStats

What does this have to do with a hospitality-focused blog? It serves two functions. 1) Whenever you can introduce a “Goodfellas” quote into an article, you do it. 2) Substitute a hotel in for a restaurant, and a lot of owners right now might have the same inclination—figuratively, of course. (I am by no means advocating arson. Period.)

I don’t own a hotel, but I can only imagine a hotel owner’s face the past few months after perusing the P&L. Something like Macaulay Culkin’s face-in-hands pose in “Home Alone.” (Not a movie I readily try and involve in anything I write. But it served its need here.)

Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” has nothing on a 1,000-room-plus downtown corridor full-service hotel.

The horror (“Apocalypse Now”).

Earnings Season

Employing moviedom helps frame the current state of affairs inside the hospitality ropes. Earnings season puts it further in focus.

Second-quarter earnings season is off to a rough start, understandably. And if they are anything similar to how U.S. gross domestic product trended in the quarter, it does not bode well. COVID-19 on its macabre wings touched down and in one fell swoop laid waste to the hotel industry, snuffing out demand for lodging accommodations, which, in turn, put both revenue and profit on ice.

It’s been a slippery slide down ever since.

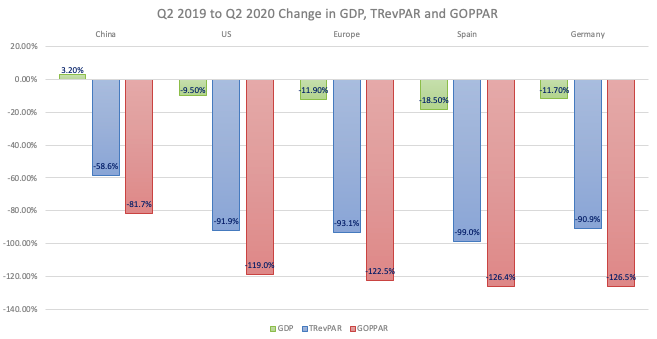

Quarterly operational data has made the collapse clear in the U.S. and elsewhere, according to HotStats metrics. In the U.S., Q2 total revenue per available room (TRevPAR) was down 93% YOY to $20 and gross operating profit per available room (GOPPAR) suffered the ignominy of falling below zero to $-24, a decrease of 122% over the same time a year prior.

In Europe, TRevPAR was down 93% to €13.18 and GOPPAR foundered into negative territory at €-16.74, a 122.2% decline from the same period a year ago.

Meanwhile, China recorded positive GOPPAR ($7.55), but still down 81.7% versus the same quarter in 2019.

These are figures that no one would ever consider possible, but illustrate the sheer delicacy of the hotel industry, where a slight jolt can wobble it and a tidal wave, such as COVID-19, can drown it. If the hotel industry was the Death Star, COVID-19 was the two proton torpedoes that blew it up (“Star Wars”).

Connection to GDP

If there is one thing that has been all but proven it’s this: Hotel demand has an undeniable relationship to GDP. Fluctuations up or down in GDP similarly impact demand for hotel rooms, sometimes a relationship greater than 1 to 1. The Great Recession proved that; where hotel demand decreased more than four times as fast as GDP decreased.

Why does this matter? Well, Q2 GDP numbers across the globe were abysmal. The U.S. economy shrank by an unprecedented 9.5 percent from April through June, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The decrease is purportedly the fastest quarterly rate fall in modern record-keeping.

The fall was greater in Spain, where the economy dropped 18.5%, according to the National Statistics Institute (INE). It’s the largest quarterly drop since the days of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

In Germany, GDP decreased 10.1% compared to the previous quarter and by 11.7% compared to the same quarter from 2019, reported the Federal Statistical Office Destatis. It’s reportedly the largest fall since 1970.

In sum, Europe’s economy shrank by 11.9% in the second quarter, the worst on record.

The one anomaly was China, which recorded positive growth in GDP of 3.2%, though some question the number’s validity.

Click HERE for larger image.

The global macroeconomic state is distressing. Meanwhile, second-quarter earnings are trickling in and the news is similarly poor.

One of the first to report was Wyndham Hotels & Resorts. The franchise company, whose brands fall mostly in the select-service to economy space, saw net revenues decline to $258 million from $533 million in the second quarter last year. On the bright side the result beat analyst predictions.

While revenues were at least positive, profits were not. The company posted a loss of $174 million in the quarter compared to a profit of $26 million in the same period last year.

Since Wyndham operates within spaces that were less impinged by COVID-19, compared to the full-service segment, expectations were that hotel companies such as Marriott, Hilton and Hyatt, likely will report worse numbers due to their exposure in the full-service and upscale to luxury markets.

Hilton’s net loss was $432 million for the second quarter, as RevPAR decreased 81% against the same quarter a year ago. “Our second quarter results reflect the challenges that our business has experienced as a result of the pandemic,” said Chris Nassetta, president and CEO of Hilton, however adding that occupancy is improving as restrictions lift and properties reopen. Occupancy in the quarter was 24.4%, 55.9 percentage points lower versus Q2 2019.

On the ownership side, the largest lodging real estate investment trust in the U.S., Host Hotels & Resorts, swung to a net income loss of $350 million in the quarter. The one bright spot was incremental growth month-to-month in occupancy and average daily rate. Occupancy was up 380 basis points from 6.9% in April to 10.7% in June. Rate, meanwhile, improved by more than 50%, from $129 in April to $194 in June.

Baby steps.

The hotel industry is governed by the principles of supply and demand, but sometimes not. Four years ago, Arne Sorenson, CEO of Marriott International, made the prescient claim that there has never been a supply-induced recession. And that it is always about demand declines.

Bingo.

Amid the pandemic, supply has no bearing on infinitesimal occupancy rates and languishing profit margins. What this disease has highlighted is not just the hotel industry’s vulnerability, but the ability of hoteliers to adapt to an unprecedented situation. To borrow again from cinema, it was all about: “Cut!”

The industry’s largest expense, labor, was the first to be attenuated. Indeed, in the U.S., payroll costs were down 70.4% in Q2 versus the same period last year, according to HotStats data. Other costs, including utilities, which were down 43% in the quarter, dropped dramatically.

While cutting expenses altogether and perpetually is not a sustainable plan (and in this case a byproduct of the times more than a strategy), it’s part of the process. A process that essentially is starting from scratch and will take the cooperation of all departments to overcome. It’s akin to a professional sports team rebuilding.

In 2013, Sam Hinkie, then the general manager of the Philadelphia 76ers, of the National Basketball Association, embarked on what became known as “The Process,” a top-to-bottom reclamation project of the basketball team with the grand intention to win a championship title. While it hasn’t bore fruit yet, it was a blueprint for trying to get things right. The hotel industry now finds itself in a similar process to recapture past success. Adapting to the new normal (enhanced cleaning protocols, social distancing) means understanding your customer matrix and recalibrating the business mix to capitalize once demand pops—whenever that is.

The last major event to disrupt the hotel industry was the Great Recession, between 2007 and 2009. The hotel industry was rattled, but never caved and, subsequently, had a stretch of strong, uninterrupted years of operational excellence.

Toward the end of the recession, Bjorn Hanson, then the dean of New York University’s Preston Robert Tisch Center for Hospitality, Tourism and Sports Management, during the 2009 NYU Hotel Investment Conference, described five factors created by the global economic crisis that might play a role in creating a reset of the demand curve:

- Long-term deterioration in consumer confidence

- Higher consumer savings rate

- Consumers trying to recover lost investment

- New patterns of behavior

- Proposed levels of tax increases affecting disposable income

As mentioned in this article, shocks to the system are followed by a reset of the demand curve, whether be it a “snap back” or resumption with a “closer correlation to GDP at a lower level.”

What can’t be ignored by hoteliers is that monumental disturbances (9/11, Great Recession, COVID-19) are a deep and lengthy blow to revenue and profit. HotStats looked at revenue and profit recovery for the UK market post 9/11 and Great Recession. On a 12-month-moving average, post-9/11 revenue recovery (TRevPAR) was achieved in 3.5 years’ time compared to more than 6.5 years for profit (GOPPAR). Meanwhile, the revenue recovery subsequent to the Great Recession took just over 4 years, while profitability didn’t come back for 6 years and 4 months.

Most agree that the post-COVID recovery could be even longer. And though GDP has historically correlated to hotel demand, this time around, it may have nothing to do with the economy, stupid.