Per the name, the historical role of revenue managers has been to maximize revenue – specifically rooms revenue or RevPAR. RevPAR growth is achieved by increasing occupancy and/or average daily rates (ADR).

NB: This is an article from CBRE Hotels

Basic economic theory says that prices influence changes in demand (rooms occupied). Depending on the date and market conditions, an increase in ADR typically tends to mute, or reduce, changes in demand. Conversely, a lowering of ADR will most likely stimulate demand and increase occupancy. Historically, revenue managers have adjusted ADR to find the best mix of occupancy and ADR that will maximize RevPAR.

In recent years, the role of the revenue manager has expanded. Revenue managers are now charged not to just maximize revenue, but profits as well. With the aid of multiple data sources, sophisticated models, and article intelligence, revenue managers have mastered the science of maximizing revenue. However, they are still learning to master the maximization of profits.

To assist revenue managers, CBRE Hotels Research analyzed the impact of the components of RevPAR (occupancy and ADR) on changes in profits. The data studied came from CBRE’s annual Trends® in the Hotel Industry survey of hotel operating statements from thousands of hotels across the U.S. The study sample consisted of 2,799 properties that participate in the Trends® survey each year from 2011 through 2018. In 2018 the sample averaged 208 rooms in size, 75.3 percent occupancy and an ADR of $170.02 ADR. For this analysis, profit is defined as Gross Operating Profits (GOP).

Finding The Optimal ADR

Our analysis examined the differences in optimal ADR setting for the revenue-maximizing versus GOP-maximizing revenue manager. The difference between the two is in the consideration of additional costs and ancillary revenues produced by additional occupancy. Assuming that in the usual range of operating values, the additional cost of accommodating another guest is more than the non-rooms revenues generated by that guest, the omission of the costs from the revenue-maximizing manager’s decision making will inevitably lead to an ADR that is lower than for the GOP-maximizing manager. For a set of hotels, or potentially even from a single hotel over enough time, the difference can be estimated directly.

For the study sample, the difference we found was $6.04, estimated with a great degree of precision. This amounts to nearly 4.0 percent of the nominal average ADR achieved by the sample over the eight-year period. On the margin, this 4.0 percent increase would discourage some guests, and therefore lower occupancy. However, the remaining guests would be paying a higher rate, and the expense of servicing the discouraged guests is not incurred. The net result is a greater level of GOP.

The results of this analysis only reflect the optimal ADR differential for the aggregate of the 2,799 properties. The differential for individual properties can be calculated using similar methods and will depend on that property’s marginal costs for accommodating guests, and the opportunity for non-rooms revenue.

Balancing Occupancy And ADR

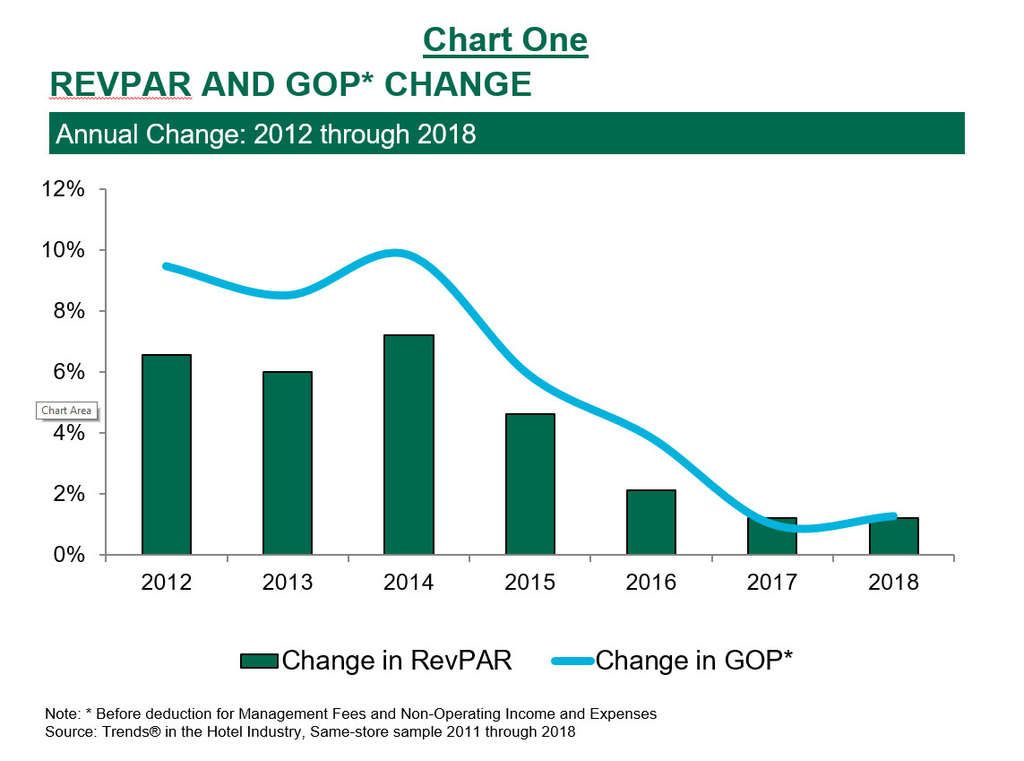

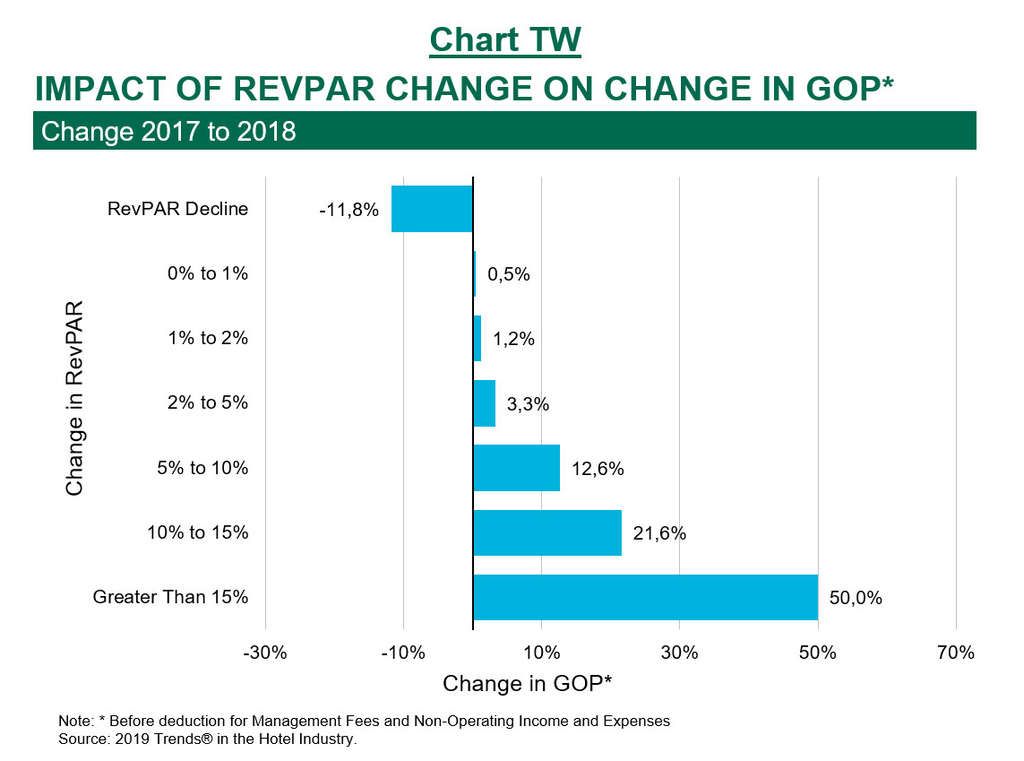

While we find there is an optimal ADR that maximizes growth in GOP, we also know that the greater the gain in RevPAR, the greater the gain in profits. As shown in Chart One, annual changes in RevPAR have been closely correlated to changes in GOP over the years. This relationship is even more evident when you just observe the performance of the study sample during 2018 stratified by the magnitude of RevPAR change (see Chart Two).

Accommodating more guests (occupancy) and raising prices (ADR) are the two factors that serve to increase RevPAR. The challenge for revenue managers is to find the proper balance of occupancy and ADR change to maximize GOP.

Conventional wisdom is that RevPAR growth driven by ADR is more “profitable” than RevPAR growth driven by gains in occupancy. This theory is based on the incremental variable costs associated with servicing the additional rooms that are rented as occupancy increases.

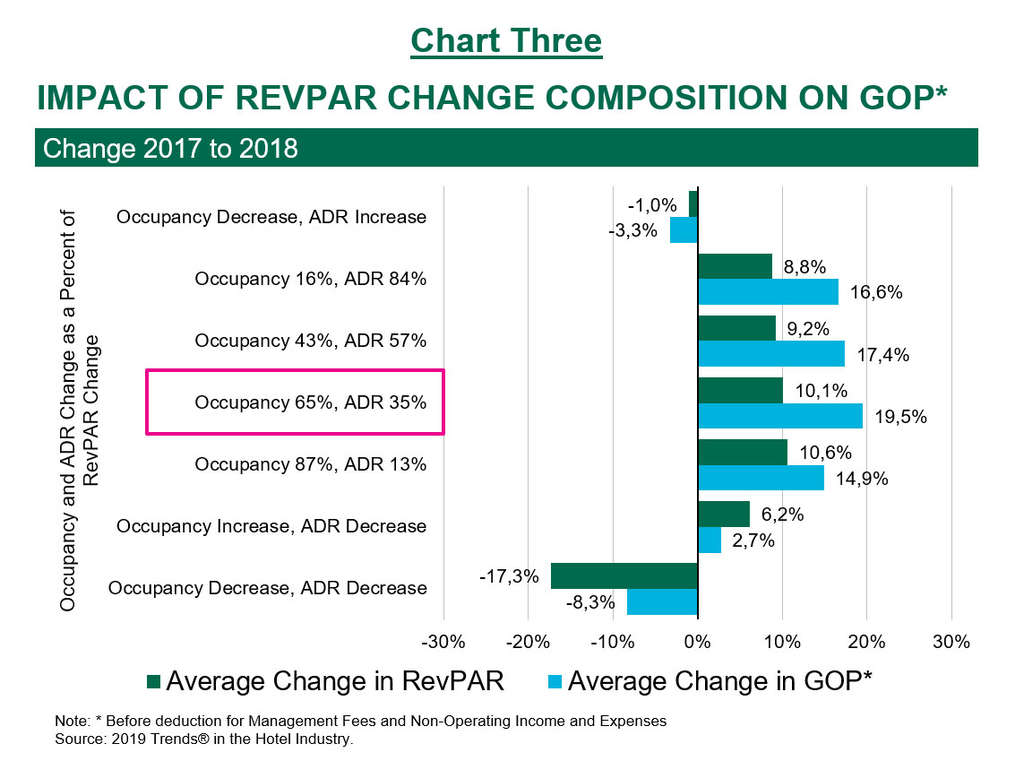

On paper, this theory seems perfectly rationale. However, in recent years, we have seen a departure from this long-held belief. When stratifying the study sample based on the RevPAR contribution mix of occupancy and ADR changes during 2018, the results confirm the recent diversion from long-standing thumb rule (see Chart Three).

Among the four categories where the hotels achieved increases in both occupancy and ADR, the GOP increase was greatest when occupancy contributed to more than 60 percent of the RevPAR growth. Further, hotels that achieved an occupancy increase and ADR decrease were able to enjoy a slight increase in GOP. On the other hand, properties that suffered an occupancy decline, but achieved growth in ADR, experienced a decline in GOP. In summary, hotels cannot live by ADR growth alone. There needs to be a proper balance between gains in both occupancy and ADR.

Challenges For Revenue Managers

Based on CBRE’s June 2019 Hotel Horizons® report for the U.S. lodging industry, ADR is forecast to increase by 2.6 percent in 2020, and 1.2 percent in 2021. Concurrently, occupancy levels are projected to decline both years.

With fewer guests staying at their hotels, revenue managers are left with ADR as the predominant implement in their toolbelt to increase revenue in a profitable fashion. More than ever it will be incumbent upon revenue managers to find the optimal room rates for their property that provide the proper balance between occupancy and ADR and maximizes GOP growth.